"It's not so much a different style of martial art, but it's a system that adapts to the American way of life"

(First appeared in Black Belt Magazine, December 1979)

People don't understand that whenever they come into contact with a child, they are potential teachers because whatever they say or do is going to have a lasting effect on that child for the rest of his life. A child's world is as real and more dangerous than the adult world because anything that is said or done is automatically implanted in the child. It stays, and we forget that."

The person quoted above is neither teacher nor psycholo- gist. He is kenpo instructor Larry Tatum. Protege of Ed Parker and a teacher in his own right

at Parker's West Los Angeles school, Tatum boasts a roster of students that includes a mini Who's Who of Hollywood celebrities. But celebrity name- dropping is not the kenpo instructor's forte-he would rather discuss the state of kenpo and the role he believes it holds for teaching children. Especially children, for Tatum explained at length to B LACK B E L T recently what he sees are the dangers of modern American society and the ameliorative effect kenpo may have on impressionable youngsters.

A student of kenpo for more than a decade and a half and now a teacher for the past five years, Tatum has developed his children's teaching methods and philosophy to the point where he has said he is now ready to publish a book on the subject called Confidence. A Child's First Weapon. Tatum said the book will be put out by Rand McNally, a national publish- ing house specializing in school texts.

Tatum said that one third of the students who pass through the doors of his' West L.A. school are children-some of whom are as young as three and a half years of age. He said that parents do not really question whether three and a half years is too young-but some do wonder if their children can really perform martial arts techniques at all-

"The trouble is that we begin teaching our children too late in the use of their bodies," the thirty-one-year-old instructor complained. "Balancing we start way too late. We finallystart at a point where their bodies have developed to the point where they've developed certain habits. Even as young as three and a half or four years of age, they already have their own ways of running, their own ways of throwing a ball, their own ways of kicking that are not necessarily right."

Tatum explained that cl1ildren are consciously and continu- ously taught reading and writing skills throughout their ele- mentary school years but that sports and physical skills train- ing were literally catch-as-catch-can affairs out on the school- yard playing fields during recess periods. The kenpoist said that only a few-and he said he had been lucky to be in this minority group-children really had natural sports talent. In the end, he added, it was this sports "elite" that gained the extra edge in high school and college where sports programs favored them at the expense of their less talented but still just as eager classmates.

"Only the elite are trained in sports, although all of us are trained to be somewhat proficient at reading and writing," Tatum said. And he insisted that education is equally neces- sary in sports and physical activities as it is in mental pursuits. The instructor said his task was to bring this about through teaching the very young-not to be martial artists, necessarily, but to become better acquainted with their latent physical skills.

"My little baby, Brittany, she's 17 months old:' the kenpo teacher explained. "While we're teaching her to talk, we're also teaching her how to do kenpo karate. My wife, Jill, is also a purple belt in kenpo."

Tatum said that with such small children-in reality, almost infants-his style of teaching must be radically different.

"It's a game, I teach them a game," he said. "Obviously, there are rules that I make them go by so that I can accom- plish my teaching, but there's no pressuring them. I teach them only as much as I know they can absorb, and th&n I don't push them any further .

"When I'm teaching children under six years old, the thing I'm teaching them is coordination-and concentration. I'm just using the art as a vehicle, that's all. That's all I really use kenpo for with small children."

In addition to teaching his youngsters better coordination and concentration, Tatum reiterated the bottom-line goal for all his children was to improve their confidence. The instructor pointed out that confidence would be a child's-and then the adult's defense against many of the forces he said had crossed American culture during the previous three decades.

"The complexes and the neuroses that we build up through- out the years are phenomenall" he exclaimed. "Look how many psychologists and psychiatrists are working trying to correct adults. Dammitl If only they would have had the proper training."

Tatum said he could recall many of the fads-crazes-that stirrred the American scene, and his friends, over the years, fads and events that he said gave him his purpose in teaching kenpo.

"If we look back to the fifties, we find that the type of person in our country who took karate classes was the thrill- seeker, policeman, FBI agent and street fighter each looking for a greater edge in his ability. In the sixties, the martial arts were known to be an activity that seemed to enhance one's mental capacity. It was also instrumental in giving rise to other Eastern cults in our country involving the mind and body. In the early seventies, it became a craze that turned into a storm only to find the substantial schools weathering the onslaught of unqualified instructors.

"Today, we have the art by itself," Tatum continued. "It's benefits are numerous, but when coupled with academic structures as it is today, it becomes a tool of immeasurable importance."

Tatum added that he and other martial arts instructors were seeing "Mr. and Mrs. America" finally come to study the various arts-and bringing their children. And Tatum said he loves teaching children.

"When I was in elementary school, I used to take kids on little tours of the neighborhood and explain certain trees and houses and so forth like this because I enjoy teaching," Tatum said. "But I think that if I can get across to pe()ple to look be- yond the veil of their man-made environment, then they'll begin to find their own potential."

Regarding teaching youngsters, Tatum said the key was ". ..Patience. That's the hardest thing. I get down on my knees, and I get face to face with them. I don't-and this is very important and will go into my book-1 never talk to the child like an adult. They don't talk to each other like that. Why in the world do we adults talk to them like that?

"I talk to them exactly like they talk to each other. It's very simple and to the point. Sometimes I use slang terms, anything they may use on the schoolyard or whatever. You must get their attention, so you've got to speak their language before you get through to them. I get on my knees, and I let them hit me. I let them block my punches. They get to hit me and kick me-it's worth it.

"If I stood up and taught them from a standing position, all they'd learn would be to follow the leader, follow what the instructor says, and that would not be teaching them," Tatum a~ed. "I want them to be able to improvise because-and I'll be redundant-their world is a very dangerous world because it's their forming years."

Tatum said he is happy to have parents watch the lessons, but he added that he was quick to keep them of; the mats should they offer advice or register concern.

"Once in a while, they try to become involved:' Tatum said. "I'm very firm. I don't ask the parents, I tell them to please go over and sit down. When the child is on the mats, that's his time. If he gets bruised or gets the wind knocked out of him, he cries. When he'~ done with it-and there's nothing wrong with crying because that's nature's kiai-they get back up. Crying is the only thing that protects them and keeps them going. You've got to release that energy. Some parents tell their child to quit crying and to get up and be a man. That's baloney! He's going to get up and be scared to death. Let him cry. He'll wipe his eyes and get up."

Tatum said he believes that this early training-all designed to improve a child's feelings of confidence and physical abili- ties in general-paves the way for their progress through an especially difficult time in their lives. He said many of his friends had a particularly rough transition through this period and often fell prey to drugs.

"During stress, logic becomes overshadowed by emotion:' he said. "Drug abuse is only one precipice one can falloff but one that vividly shows why the martial arts can play an impor- tant part in the rechanneling of one's life.

"Adolescence is that awkward time of life. The transition from childhood to adulthood is never easy. Childish pleasures no longer satisfy. One's social standing becomes dependent on the approval of others. Comparison becomes rampant, and some find they lose their own identities. Peer pressure mounts seemingly beyond endurance, escape is sought, but the avenues are limited. For many, escape is through drugs.

"If a child is to become an adult," Tatum went on to say, "then he or she must be trained to meet and solve the prob- lems of growing up. Kenpo karate and other martial arts do not offer answers to each individual problem. But through acquiring respect in a healthful and intelligent environment of planned progression, a child or young adult begins to build confidence. The confidence shows them they need no longer be subject to the whims of others."

Some of the children Tatum said he teaches are, in fact, the children of parents who themselves studied kenpo at the same school more than two decades ago. Tatum said he had such a full schedule of classes that callers had to make appointments to see him, a statement BLACK BEL T can verify. Some of Tatum's students include Hollywood notables including Sidney Poitier, Elke Sommer, Scott Jacoby and Edd Byrnes. And many of Ed Parker's original students are returning for more instruction from protege Tatum.

As with Parker, T atum said he places great store by the use of analogies drawn from daily experiences in order to point up the key elements in what he teaches. Most techniques have colorful names kenpoist Parker devised to aid students in re- membering and performing the moves accurately and without hesitation (see BLACK BEL T issues of July, September and August 1979 for the feature on Ed Parker and his techniques). The younger kenpo teacher said the use of analogy was especi- ally valuable in teaching children.

"When dealing with children, I have found that key words play an important part in bringing about a desired response," he said. "Obviously, the arts require certain amounts of aggres- sion, whether defensive or offensive. Too often, aggressiveness is mistaken for violence, and a child will purposely refrain from emotion. Such words as faster, harder, stronger lose their effectiveness because of overuse. These are words that a child expects to hear, so the instructors may never break through."

But Tatum said that there were ways to, in fact, break through. "For one child, it was the phrase, 'first gear ,"' he said. "I told him to get out of first gear and into second. His mother came in the next day, and my student said he would ask her what gear she was in while she was driving. She ex- plained that the different gears made the car move faster. At the next lesson, he not only moved faster but at different rates of speed.'

Though Tatum directs much of his effort at teaching young children, he nevertheless maintains that he wants kenpo to be an art for the well-educated.

"In the orient, martial artists are very literate men," he ex- plained. "They were very learned men, well-educated before they became noted as martial artists. That's the way it was, and that's what is now happening here.

"I have Addison Randall and Rick Hughes working for me as assistants, but it took me a long time to find them," Tatum noted. "I hired and fired quite a number of teachers to locate these guys because I couldn't have an illiterate man teaching literate people. You can't do that."

Tatum said he needed intelligent instructors so that they could pursue more than mere punches and kicks in classes. "I've got to teach him (his students) not only physically and teach him how to concentrate, but I have to adapt the teach- ing to his attitude," Tatum said. "I don't know if he is the type of guy who could kick somebody in the groin or a guy that in a dire situation would be able to poke somebody in the eye. I have to find out if he is, and if he is not, then I've got to teach him in a way that I want. I don't want him to think that he's learning a violent thing. There's nothing violent about what we're doing, but if there's malice behind it during prac-tice, yes, it's violent.

"But when I teach I have to know the person's bc ground," he said. "I've got to know if he's ever been in a fi! How do you get him to pull it off if he hasn't been in an vironment where he has kicked somebody?

"You draw analogies. You can't take Mr. and Mrs. Amel and put them into a karate school and teach them all ti" moves and expect them to pull it off in a street situatiol they don't associate it with their environment. They havE associate it with things they have learned."

Tatum commented on the claims some have made tha takes too long for average students to master kenpo mc and thus obtain rankings and proficiency. He explained v these claims 'f"ere made.

"Kenpo is not just a style, it is a system:' he maintair "Kenpo incorporates kicking, punching, off-balancing, ti ping the hands, flipping, throwing, wrestling, pressure poin everything. It takes longer to earn a belt in kenpo, and w' noted for that, but the thing is, you become a well-roun, student. If you were to go from style to style-people 01 prefer cetain styles-that would be fine. These people r like a portion and keep that for what they do. But Ed (Parker) set up Kenpo as a system." .

Although Tatum insisted that kenpo techniques forme total system of martial arts, he said that no student need E master the totality. "He doesn't, he only takes the criter the instructor explained. "There's a certain criteria he ha! learn-the sum of the basic kenpo techniques and strategies- but he only takes certain portions of that and adapts it to his body build, his style and again, his attitude so that the sys- tem works for him. He doesn't have to go from school to school till he finally finds one style that works for him. If he comes to a kenpo school, anything will work for him, but he'll use only those elements that are really effective for him. That's the difference between a style and a system."

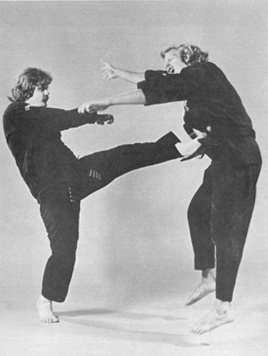

By example, Taturn noted another comment often aimed at kenpoists that they rarely employ high kicks. He insisted that tournament kenpoists do employ the flashy high kicks-as taught in his school-but that for many, the choice is for the low variety which is more effective in street confrontations.

"They both have their place," he said. "In a tournament you need high kicks, but in a street situation, low kicks are harder for your opponent to see and to block. If you used high kicks here, you wouldn't be able to use your arms simul- taneously, but when you kick low, you can kick him in the knee and punch him in the face at the same time."

No matter how effective a person's use of kenpo techniques may be, Taturn placed a high premium on one more quality, albeit one that for many is quite intangible-almost mysteri- ous: ki. The kenpoist said that he believed everyone possessed ki but that only a few people ever called on the ultimate re- source. And even then, those individuals only found ki for an instant-at the height of a physical or emotional crisis when a surge of strength was required that otherwise would not have been available.

"Yes, they found out that their well was deeper than they thought, and it was unexpected," Tatum said. "But that doesn't mean they can use it all the time. Only the mastery of ki allows somebody to tap that energy at will without getting emotional or all stressed up."

T aturn explained how his instructor, Ed Parker, developed ki strength at the outset of his teaching career. "He didn't in- vite challengers in, they came in. What happened to him hap- pened to me, because when Ed personally quit teaching and put the teaching on my shoulders, I was under challenge again. And for the first year of my teaching, I had people coming through that door right and left. Under that stressful situation, I had to pull energy from my spirit, it boiled right down to that.

"You are working with your spirit, your etheric self. It's almost transcendent, but the energy is here. Most of us live out our lives, and though we have the energy, it's latent. It's there, but we don't use it because our environment doesn't demand it of us. If I hadn't become a martial artist and was on a desk job, then I would never have used that energy. I would have never had to force it out. But because I became a martial artist, it began to move. Well, with all these people coming through the door to challenge my teaching Ed's kenpo, I had to go up and beyond. I had to bring it back up and force my body to do it again.

"There are talents within all of us, but unfortunate.ly, our environment is like a veil, and most of us never reach our potential."

Taturn said there were certain kenpo techniques designed to enhance latent ki energy, but he insisted that the energy to come from within. And this, among the various techniques, is what he said he tries to impart to "Mr. and Mrs. America"- and children.

"That's kenpo!" he exclaimed. "That's what Ed, the other kenpo practitioners and I have been trying to tell people. It's not so much a different style of martial art, but it's a system that adapts to the American way of life."